It’s 9am. I’m on a subway ride to hell, or Times Square, which is the same thing. I’m staring straight ahead and hoping the ride lasts forever. I’ve taken out my septum ring and my earrings are sensible studs; I’m even wearing a blazer and a tie. It feels like a costume because it is. I’m dressed up as an adult man going to an adult job in a windowless office.

I’m working in the communications department at a prestigious law firm. When I heard about the position, I was sure that there was no way I’d get it – I’m underqualified and I have zero interest in law. I applied anyway and took the interview as practice, feeling a rare lack of self-consciousness. Then I was hired, which means that now I have to figure out what the fuck I’m doing there. I’m failing. I’m habitually late; I alienate my coworkers; I don’t complete simple tasks. One day, I attend an utterly pointless meeting and I fall asleep. Whatever.

When I arrived in New York at 18, I was certain that I could take on the city. Now it’s 2016 and I’m 22, feeling like just another rat in a sea of rats. Life is a dark corridor, a cold and empty blur. I can’t distinguish August from October. I don’t know who I am or what I’m doing; I feel lost and alone, unable to comprehend or reach for what I want. Everywhere I go, I have headphones in.

When I look back on this time, I can hear The Roches singing.

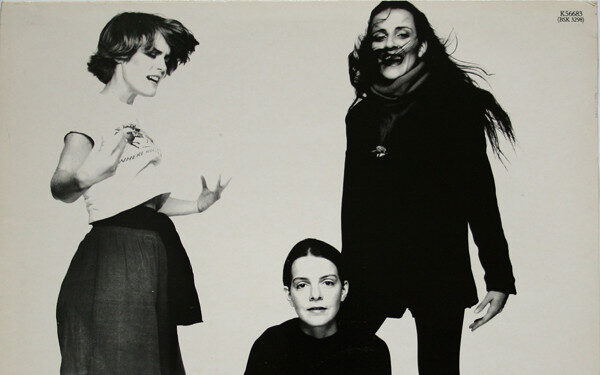

The Roches were a group of three sisters – Maggie, Terre, and Suzzy – who released their self-titled debut album in 1979. The songs on it illuminate simple, quotidian narratives with complex harmonies and grounded humor.

In 2016, I was obsessed with this album, with the stark beauty of their voices singing together, with the playfulness and blunt honesty of their lyrics. They sum up the thing that I liked most about them in a 1989 interview with the radio DJ Ed Sciaky: “We’re into reality.”

One of my favorite songs is “The Train,” the sixth song on the record. Its subject is so boring, so real, that it’s funny: Suzzy gets on a hot, crowded subway and sits next to a dude. The group doesn’t try to embellish this concept with unearned pathos or gaudy musical ornamentation. Its brisk tempo and rhythmic scratch guitar imitate the thrum of train wheels, while the lyrics are some of their most plainspoken, forgoing rhyme for everyday detail. It makes the song feel grounded and relatable; Suzzy even ends the first verse by remarking, “Now, everybody knows the way that is!” I’m charmed by the way she sings that line with an affected folksiness, as if she’s downplaying her experience. But the harmonies that bloom behind her cut against any self-deprecation: her sisters respond to her to say that yes, they understand, they’ve been there too.

Their harmonies nudge the song away from Suzzy’s individual perspective, toward an emblematic expression of a larger, shared feeling. Later, Suzzy confesses that both she and the man next to her are miserable in the crowded train. She’d like to ask him his name, become friends, make the best of a frustrating situation. But she doesn’t, because – and here the guitars drop out, leaving just the women’s voices – “I’m so afraid/Of the man on the train.” Maggie and Terre harmonize the first half of the line, then stretch out the word “afraid” into pure vocalization, leaning into the hugeness of the word and the feeling it describes.

That feeling points to a potential for violence or pain, but that potential remains latent. After the second chorus, the three spiral off into whimsical ad-libs before reuniting on a descending “ahh” harmony that’s half-scream, half-sigh: a pressure release. Their fear and paranoia are sublimated into playfulness. Ignorant of their feelings, the train rumbles on.

Sitting on the train, listening to “The Train,” I stare out the window when the tracks surface from underground between 138th and 116th. The sun glances off the Hudson River, too bright in my tired eyes. But I love this view. I look across the river to New Jersey, the cliffside covered in red and gold trees. For just a moment, I can imagine myself as I want to be: fresh, ambitious, on the way to a new day. Then we go back underground and I see my unshaven, worn-out reflection. I see myself the way everyone else will see me. The train reminds me: I’m not who I should be.

“Mr. Sellack,” one of Terre’s contributions, feels like this too. It’s like a reminder, or a realization, that whatever you might want or imagine for yourself has to fade next to the insistent reality of what is. The song is about begging an old employer to get a restaurant job back, with a mixture of rueful humor and desperation. The guitar lead squiggles and trips over itself, cartoonishly eager, while the chorus winkingly assures Mr. Sellack that no task is too demeaning: “I’ll clean the tables/I’ll do the creams/I’ll get down on my knees and…” (pause) “…scrub behind the steam table.”

But even in this dispiriting setting, existential anxieties and transcendent aspirations peek through. After Maggie delivers the line “Give me a broom/And I’ll sweep my way to heaven,” the trio burst into an impeccable three-part harmony, like heaven itself is backing them up. It’s a great joke, but there’s something raw and bitter beneath it – elsewhere, they sing that “Since I’ve seen you last/I’ve waited for some things that you would not believe/to come true.” If angels are on their side now, where were they then?

The wistfulness and confusion beneath the song’s blithe surface are real – like, sourced from real life. In the Ed Sciaky interview, Maggie and Terre discuss their first record deal, which they signed as a duo. Their lush, ambitious album Seductive Reasoning was released in 1975, but the record didn’t do well commercially, and the process of making it was difficult. Terre notes that they spent a year and a half working on it, and that they had to fight with the label just to play their own instruments on the songs that they wrote. When Sciaky asks what they did in the four years between that album and the release of The Roches, Maggie sighs, “We just worked jobs…” And as silly as it might seem, the resigned way she says this gives me so much comfort.

In 2016, I know that I’m lucky to be where I am, to have the opportunity I’ve been given. Even though I’m working in a contract position, the pay is good and there’s a path to a long-term job if I do well. Stability is in my grasp; I’m fumbling it badly. I know that my discomfort reads as lazy carelessness, like I’m indulging myself instead of struggling. But, whether it’s because I had imagined something different for myself, or because I’m not used to the idea of placid everyday existence, or because I don’t understand my coworkers or the standards of behavior and presentation here, I am struggling. I’m just not sure that that matters.

“Mr. Sellack” ends with the group imitating the sound of a steam train, emphasizing its thematic connection to “The Train”: both are songs about being trapped in a situation by forces larger than yourself. But where “The Train” makes that entrapment literal, in the sense that both Suzzy and the stranger are in the same physical space, “Mr. Sellack” is about being metaphorically or spiritually trapped – they’re stuck in the same old job, driven by the caprice of the record industry or the whims of an uncaring God, which might be the same thing. It’s a psychological study of limbo, where the sisters’ cheerful good humor has to stretch to cover the magnitude of their frustration.

But sometimes they can’t quite stretch far enough. To my ears, one of the best songs from the album is “The Married Men,” which was written by Maggie. There’s a slippery quality to this song, reflecting back whatever emotional narrative you feel like projecting into it. It’s not vague or imprecise, but it lacks the playful levity of a song like “Mr. Sellack” or “The Train” – its humor is dryer, and darker. It indicates a space so vast that it swallows up everything you could throw at it.

I didn’t hear all that on my first listen, though. The song’s delicate guitar parts lock together in an intricate mesh, while its rhythmic lilt reminds me a little bit of bossa nova; the effect is pleasant, unassuming, even pretty. Maggie usually sings a low harmony on other songs, but here she takes center stage. Unlike Suzzy’s theatrical phrasings or Terre’s shimmering clarity, Maggie’s contralto is nearly affectless, and her voice acts more like a vehicle for meaning instead of an interpreter of it. So when Maggie sings the first verse and chorus of “The Married Men” solo, her performance asks you to pay attention to her lyrics.

Over time I realized that those lyrics, in their impassivity, are the album’s most confrontational. “The Married Men” is a song about fucking married men, viewed dispassionately; there’s no self-recrimination, nor does Maggie romanticize what’s happening. Her writing is factual and direct: “When they look into my eyes, I know what to do/I make sure the words I say are true,” she sings, sphinxlike. When she delivers the song’s title, her voice travels up to the top of her range, then descends downward, like she’s testing out how the words make her feel and viewing the situation from different angles, at a distance. Then, half-joking, she shrugs, “Never would’ve had a good time again/If it wasn’t for the married men.”

Contrast the Roches’ version of the song with Phoebe Snow and Linda Ronstadt’s cover on Saturday Night Live, which is ornamented with wistful chimes, weepy violin, and long, expressive vibrato singing. Snow and Ronstadt’s musical choices give their version a coherent arc from indulgent loneliness to bohemian disregard. They imbue the song with a level of commercial beauty that the original lacks. But to me, that lack is exactly what makes the Roches’ original so compelling: the song sounds pretty, but it rejects the pop imperative of beauty.

“The Married Men” forecloses the possibility that we, as an audience, could understand Maggie’s choices. Despite writing about a vulnerable situation and relating it through the vulnerable medium of singing, in this song she refuses vulnerability. It’s about being unavailable.

When I feel alone, or when I want to feel alone, it’s a song that I return to. I’ve sung it at open mics, at concerts, to myself on the train, alone in my room screaming the high notes.

In 2016, in the office in Times Square, one of my first tasks is to read through social media mentions of the firm in connection with a high-profile sexual assault case involving a famous musician. All this digital text blurs together; the words are meaningless. I stare at the screen and I see myself in it. When I get upset or – worse – bored with this, I walk to the break room to grab a cup of coffee. All the hallways leading to and from the windowless room are covered in reflective glass; I stare at the wall and I see myself in it. But I don’t want to be seen at all.

Shortly after I moved to the city, I fell in love for the first time. Over the course of our relationship, the man I loved would assault me multiple times, would verbally abuse me, would find ways to play on my fears and vulnerabilities so that he’d have access to my body. I treasured his rare gestures of kindness like they were diamonds; I thought we would be together forever. I was in school when our relationship ended, which meant that I was too busy to process what had happened. But even after graduating, when I think that I should be able to move beyond it, I still feel like I’m on unstable ground. I’m afraid to imagine who I might be in the absence of someone else’s control. I’ve only just begun to figure out that I don’t want to be controlled.

I spend some of these cold, blurry nights with a different man who lives in my neighborhood. He’s not perfect, but he treats me with tenderness; he makes me feel desirable, not just desired. I know that he cares for me, and I care for him too, but I intentionally close myself off to him. Some kind of change is coming; if he loves me now, there’s no guarantee that he’ll love me later. I want to experience pleasure, not vulnerability, not understanding. I’m so far off from understanding myself.

On “The Married Men,” Maggie sings, “I am just an arrow, passing through.” I think about this line all the time. Within the song, it’s about how she’s not permanent in the lives of the married men, just a fleeting presence. But it feels like it’s a message to herself, too: an assurance that the person she is now, here, doing these things, feeling these ways, is impermanent. The woman that these men turn her into is only who she is with these men. Maybe Maggie likes being this woman. But even if she doesn’t, she’s still curious about her.

This curiosity seeps into every song. All across the album, the Roches’ sense of play – in their lyrics, in their harmonies – disarms the world to such an extent that they can navigate experiences of fear, humiliation, boredom, and pain with an analytical and nonjudgmental eye. Each moment is assumed to be worth investigating simply because each moment is real. The rigorous consistency of this approach suggests the existential meaninglessness beneath all of our attempts to make our lives seem dramatic and interesting. Reality, the thing they’re into, doesn’t distinguish between the spectacular and the every day, the traumatic and the prosaic: it’s all the same to the universe.

I sense a void beneath the surface of daily life, vast and dark and endless. The Roches gaze into that void, and then they come back singing.

“Hammond Song” is probably the most recognizable track here to modern listeners – it was recently sampled by The Avalanches, and it’s been covered by the Indigo Girls, Whitney, and Robin Pecknold. To hear the group tell it, the song is about the immediate aftermath of losing their first record deal; Maggie and Terre left their careers behind and moved to Hammond, Louisiana to live with a friend who ran a karate school. However, the lyrics don’t take their point of view. Instead, the song is written from the perspective of a third party. They could be a stern parent or a mentor or a well-meaning friend, maybe a sister, maybe God. Who can say?

This narrator – sung in unsettling unison – advises that if they go down to Hammond, they’ll never come back. “We’ll always love you,” they sing, “but that’s not the point.” The melody reaches up and up, incandescent, fearful, awesome. Then they change keys and Terre’s voice, alone, rings out:

“I went down to Hammond,

I did as I pleased.

I ain’t the only one who’s got this disease.

Why don’t you face the fact,

you old upstart:

We fall apart.”

On that last word, Terre jumps up an octave and holds the note as the song shifts back into its original key and Maggie and Suzzy stretch into a glowing harmony behind her. It stops my heart every time.

To be alive is to be changed. You might look at yourself on the other side of an experience and not even recognize who you’ve become. To me, this is what they mean when they say that “you’ll never come back” – it’s not that you’ll get stuck, it’s that whoever you are when you come back in the future won’t be who you are now. The you that leaves is gone forever; the you that returns is a stranger. You can never see the future, and you can’t change the past. All you can do in the darkness of the present is choose. You are always in a windowless room.

In late 2016, I am unceremoniously fired. It’s embarrassing. But when I walk out into the bracing 3pm sunset of a New York winter, knowing that I’ll never have to come back to this place again, a wave of relief washes over me. Later, I will make time for shame. For now, I take the train back home and make plans with my friends. I sleep well for the first time in months. That winter, I begin going by “Leah.”